I saw yet another post on social media the other day asking why knitting patterns cost so much. The poster was startled to find that a digital pattern cost £6 GBP (about $8 USD) and wondered what she was paying for since there wasn’t even paper involved.

So I thought it might be fun to take the opportunity to break down everything you’re paying for when you buy a knitting pattern. Strap in! It’s going to be a wild ride.

Ideation and Creativity

One of the most obvious invisible things you pay for when you buy a knitting pattern is access to the creative mechanisms of the designer’s mind.

Most well established knitting pattern designers have a fairly distinct design outlook. Whether that designer specializes in color work, size-inclusive customizable garments, lace shawls, dainty yet relaxing socks (hi!), or something else, part of what you get when you buy a knitting pattern is you get access to that unique design perspective.

This is especially helpful if you have a brain that functions differently or emphasizes different aspects of the creative process compared to the designer whose pattern you’re purchasing. It’s a quick shortcut to a knit that might be difficult to come up with on your own.

Sample Knitting

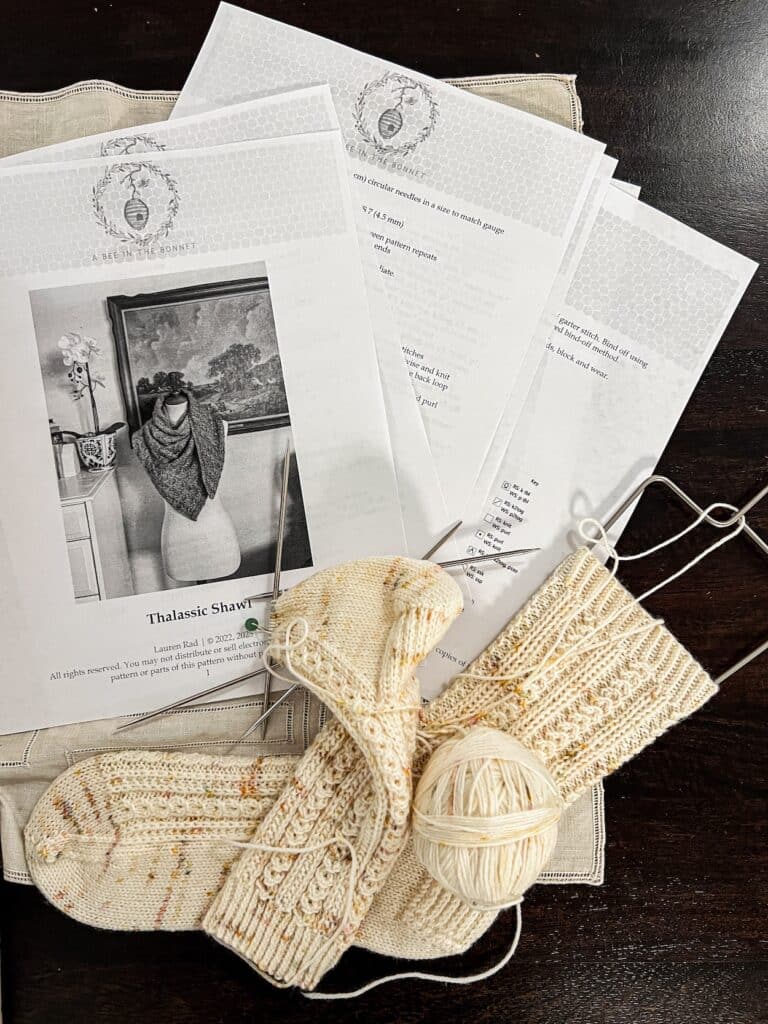

The next thing you’re paying for is the sample knitting time. This might seem obvious, but somebody has to knit the thing from the pattern. That way, you can see what it is you’ll end up creating with that pattern.

Sometimes the designer does the sample knitting. Sometimes they hire a sample knitter to help them keep up with the pace of production. In either case, that sample knitting costs time, and sometimes it costs direct money.

A sample for one of my pairs of socks can take anywhere from 13 to 20 hours, or even more if it’s a very complicated stitch pattern. Garment samples can take even longer. I did the math on a T-shirt I recently finished, and it took me about 40 hours to knit that thing.

Expertise

A pattern designer also has expertise in a few different areas that are really helpful for somebody who does not have design experience.

A designer who has done their homework knows about the types of construction that are relevant to the item they’re designing, the properties of different kinds of yarns based on their fiber content and their construction, industry norms for clear pattern writing, and the math needed to scale their design to various sizes.

All of this expertise takes time to build, and sometimes money, too. In fact, I have taken several classes and joined a few memberships to build these skills and make sure that I am providing my customers with a product they deserve.

Technical Writing

As I’ve mentioned before on social media but haven’t really talked about around here that much, pattern design and pattern writing are two totally different skill sets.

Designing a knit item, especially the sample which is only knit in one size, is a very creative process involving colors and textures and shape and drape. I do a lot of my design work based on a combination of instinct and curiosity. If I flip this stitch pattern, how does that look? What if I stack it or stagger it?

Writing the pattern, on the other hand, is a very technical part of the process. There’s a lot of math involved, but what’s more, there’s logic and graphic design principles involved. Designers need to understand headings and structure and hierarchy. Where do you put parentheses? Where do you put brackets? Do you need to explain a process thoroughly or can you just tell the knitters to use XYZ technique?

My job as a designer is to communicate as clearly as possible with as many people as possible. Because I publish digitally and sell online, that means also taking into account that I have an international audience.

For example, I publish in English. There are several different countries that speak English, though, and the same words sometimes mean different things in those countries. I need to make sure I’ve taken that into account when drafting a pattern. Then I have to make sure the pattern is also clear enough for people who don’t speak English as their first language.

Photography

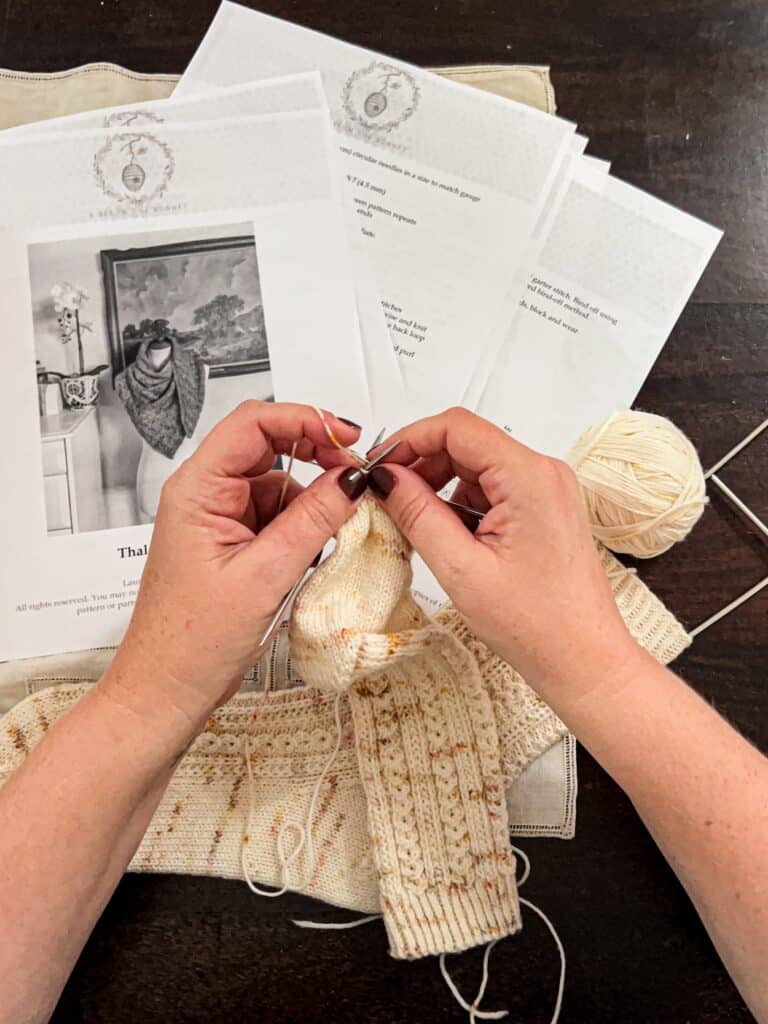

I’ll let you in on a little secret here: I love the photography part of my job almost as much as I love the knitting part of it.

That’s not the case for every designer, though, and even when you enjoy it, it’s still effort. I often find that after a good knitting photo shoot, I’m out of breath and a little bit sweaty. I’m climbing up on stools, lugging equipment around, setting up and breaking down props and displays, contorting myself into awkward positions to get just the right angle, and so much more.

Then there’s the editing process that comes afterward. You have to make sure that the lighting is consistent across pictures, the color balance matches, and the images are clear and cropped so that the subject of the photo is obvious.

All of this requires both physical effort and additional expertise. A designer will need to understand the principles of photography, including when to break the rules, and how to use editing software. More on that in a bit.

Of course, a designer could just hire a photographer–but then, that costs money again.

Marketing

When I started designing, I thought I could just post about a new pattern a couple times on Instagram, pop it up on Ravelry, and people would discover and buy it. Oh, that sweet summer child. If only I could go back in time and tell her just how much of this job is actually marketing.

Because the truth is, knitting patterns generally don’t just sell themselves. Designers need to actively market them.

As a result, the designer needs to create content for social media, send newsletters, engage with people in comment sections, create a zillion pins for Pinterest to be dribbled out over a several-month span, write blog posts, guest on other people‘s blogs and podcasts, and so much more.

For me, this is all actually pretty fun, but again, it’s still work! It takes time. In fact, I have discovered that to do it as well as I want to, it’s a full-time gig.

Bookkeeping

This, for me, is my least favorite part of the job. I do not enjoy recordkeeping. I really do not enjoy recordkeeping when it also involves finances.

And yet, it has to be done in order to run a business. If you don’t do your bookkeeping, you don’t have a business, and eventually, the designs peter out.

Some designers outsource their bookkeeping to a professional bookkeeper, which is also an expense that needs to be covered by selling patterns. Even if it’s not outsourced, though, that’s still time that goes into the bookkeeping, and the time is part of the cost of running a business that needs to be covered by the product sold.

Customer Service

When you buy a knitting pattern, part of what you get in most scenarios is access to the designer when you have questions.

This is because, even in the most careful design workshop, things slip through the cracks sometimes. There might be an ambiguous instruction or an outright error. When that happens, I’m always happy to hear from a knitter who catches it. That way, I can set them on the right track and then fix the pattern.

Sometimes, though, a knitter has questions because they’ve bitten off a little more than they can chew with a pattern. In those cases, I do still offer support where I can. It takes time, though. I usually have to dig up the pattern, read it through again to refresh myself (especially if it’s been a few years since I’ve designed the pattern), figure out what’s going on from the knitter’s email (which isn’t always clear), and then write up an explanation to help them keep moving forward with their project.

Again, this is still work I like doing! But it takes time. Are you sensing a theme here?

Physical Equipment

Running a knitting design business has relatively low demands for physical equipment compared to a lot of other businesses. We’re not in heavy manufacturing. We don’t need a warehouse for our stuff, generally speaking.

But that doesn’t mean we don’t need any equipment!

Even after almost 18 years of knitting, I still find that I need to buy needles now and then. I lose stitch markers, and then I have to buy more. Sometimes I buy the yarn for my designs, as well. That’s especially the case if it’s a project where I don’t have a clear timeline and don’t want to have to worry about coordinating with a collaborator.

But on top of the actual design materials, you also need something to take pictures and something to write patterns. That generally means you need at least a phone and a computer.

While they don’t have to be top of the line equipment, even models that are a few years old and lower down on the scale of technical specs still cost a decent amount of money. Those physical goods also need to be replaced when they wear out.

There are also physical things that aren’t necessary to a business but are very helpful to running a business. For example, a desk and a chair. Yeah, you can run your business from your sofa or dining table, but your back’s gonna start hurting eventually.

I use certain props for my photos, like a dressmaker’s form and a mannequin head. While those aren’t strictly necessary, it’s easier to take pictures that way than to attempt a bunch of selfies wearing the knit item. A lot of people really prefer seeing a knit on something that at least resembles a human body before buying the knit pattern.

Software

Along with the physical things needed to run a knitting design business, there are a lot of digital things we need. Those aren’t usually free, either.

You need software to write the pattern, including a separate piece of software to create charts. There’s also photo editing software, maybe video editing software in addition if you create video content for marketing or educational purposes, newsletter services that get more expensive the more subscribers you have, website hosting costs, and more.

While some of these are annual expenses, many of them are monthly.

Fees and Taxes

Most of us pay at least a portion of our sales to the platform where we sell our patterns. Whether it’s Ravelry, Etsy, Payhip, or something else, each of those platforms takes a percentage of each pattern sale, sometimes even before any money gets deposited in our own account. That means that while the pattern might cost you $8, the designer isn’t actually receiving $8.

If you live in a place where tax is automatically added to the purchase of consumer goods, even digital ones, you may see an even higher price for the digital pattern that isn’t actually the price the designer set for it. The final price you see includes the taxes that have been tacked on by the government where you live. Now, those taxes go to fund a lot of good things like schools and roads, but they’re not something the designer has any control over.

In fact, we also have to pay our own taxes on our end. For example, I have to pay an annual fee to my local government to maintain an active business license. That fee is based on a flat rate calculated by industry sector plus a percentage of my annual sales.

Professional Services

A good knitting pattern has been edited by a skilled technical editor. Full stop.

Tech editors, though, don’t work for free, and nor should they. They have special developed expertise that is in high demand. Depending on how complicated your pattern is, how much experience your tech editor has, and where your tech editor lives, you’re looking at anywhere from $50 to a few hundred dollars to have your pattern tech edited.

There may be other professional services associated with running your design business, too. You may occasionally need to consult a lawyer to make sure that you are protecting your intellectual property and yourself. You might need an accountant to help with your taxes. All of these professional services can be startlingly expensive.

Does a Pattern Really Cost that Much?

Before I wrap things up here, I want to push back on the idea that $6 or even $12 is so much for a knitting pattern.

The average price of a movie ticket in the United States is over $11 now. The average price of a round of golf is $40-$50 across the United States, with an average of $70 here in my home state of California. Many video games now cost $50-$80 per game.

I chose golf and video games for this comparison specifically because those are also hobbies that require additional equipment, just like knitting. With the knitting project, you still need yarn and needles. If you’re going golfing you need clubs and clothes. If you’re playing the video game, you also need a console or a PC of some sort.

So are knitting patterns really that expensive? I don’t know, but I can think of worse ways to spend your money.

Let’s stay connected!

Join my newsletter for 30% off all new releases, regular updates with helpful tips and tricks, first crack at registration for upcoming workshops, exclusive discounts, and more.

I’m on YouTube now and would love to have you join me there for regular project updates, technique tips, chats about goings-on in the knitting world, and more.

Prefer to read without ads? Join my Patreon, which starts at just $1 a month!

Join the A Bee In The Bonnet Facebook Group to participate in knitalongs and other fun community events

Come hang out with me on the A Bee In The Bonnet TikTok

Follow along on the A Bee In The Bonnet Instagram

Get inspired via the A Bee In The Bonnet Pinterest

There is also the cost of creating tutorials if needed. Those take time, careful planning, and can make or break somebody success with the pattern if they are new to the type of knitting for which you write patterns.

Personally, I don’t think you needed to do this post to justify the cost of your patterns, but it was interesting to see everything that goes into your work. I have never thought patterns were too expensive. Even without your post, it is pretty evident that a lot of work goes into patterns and it’s not something the average knitter can even do. You are an artist and an artist needs to make money. Kudos to you though for the post!

This was an incredibly interesting article!!!! One of the things I like about knitting is the math/logic aspect which comes into play just following/understanding a pattern. But, I am in awe of those who are able to write patterns!!! Just the actual development of an accurate pattern (for multiple sizes/languages/cultures) was daunting – then adding on all the steps necessary to get it out to the customer base!!! I think anyone who reads this will have a new appreciation of the value they get when purchasing a pattern. I honestly don’t know how you have time to actually knit!!!

Great article! Everything you discussed is spot on! I appreciate all you put into your business. You give us so much. Thank you!

Hi Lauren,

I fall into the category of people who don’t baulk at the price of a pattern, because (i) the designer needs to get paid; (ii) I get – usually! – so much enjoyment from knitting the pattern; (iii) I often write my own patterns – unpublished – and know how much time is involved in writing them, changing something in the design and having to re-write/re-chart, etc.

So I just wanted to take a minute to than you for writing this post and going into all the details of what it takes to have a design go from your creative mind to my (our) knitting needles!

And I hope you make enough from your patterns that you make a decent living out of them – because you absolutely should!

Patricia

PS: I DO love your photography!